The forest fires in Los Angeles have now burned over 35,000 acres, an area twice the size of Manhattan. Unfortunately in recent years, forests have become a cornerstone of global climate mitigation strategies. Governments and corporations alike have leaned heavily on carbon credits derived from forest conservation, planting, and management to offset emissions. These credits, in theory, represent the carbon sequestered by forests, helping to balance the scales of greenhouse gas emissions.

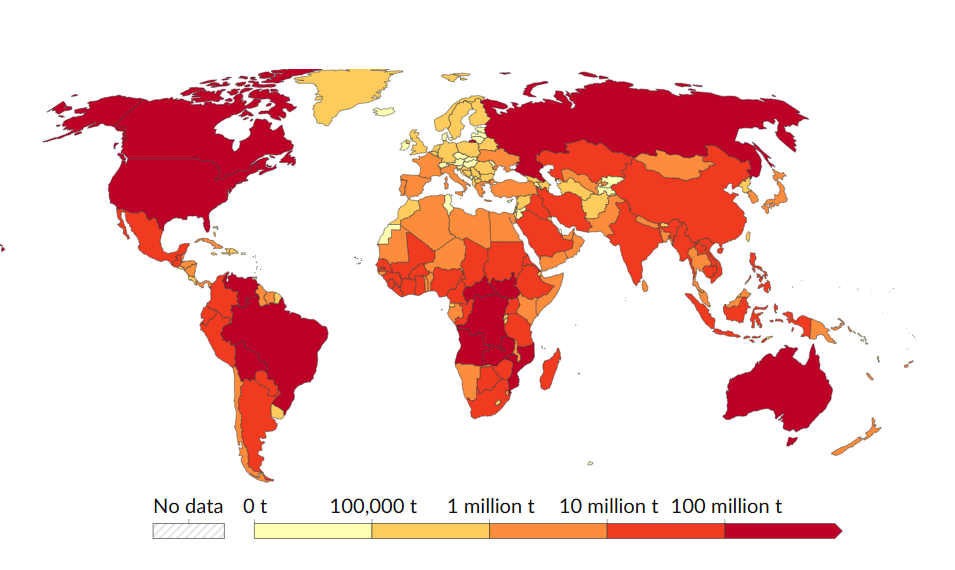

But as forest fires escalate due to climate change, the reliability of these credits needs to come under increased scrutiny. Are they as valuable as promised, or are we as a society banking on a solution that is literally going up in smoke? The following image shows the annual CO2 emissions from wild fires in 2024.

Source: Annual CO₂ emissions from wildfires, 2024, Ourworldindata.org

Thank you for recommending One Degree Apart and I’m grateful for your support.

Globally, forest-based carbon credits stem from various initiatives, including:

REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation): A United Nations-backed program encouraging countries to conserve existing forests.

Afforestation and Reforestation Projects: Credits are issued for planting new trees or restoring degraded forests.

Private Conservation Initiatives: Corporations partner with private landowners or purchase forested lands outright to claim the associated credits.

These credits are often touted as a "win-win" solution, providing funding for forest conservation while offsetting industrial emissions.

Fire Risk: Carbon Credits on Shaky Ground

Wildfires are intensifying globally, fueled by hotter, drier conditions and poor land management. When forests burn, they release their stored carbon, reversing decades of sequestration in a matter of hours or days. This raises several troubling questions about the value of carbon credits tied to forests:

Are Credits Truly Permanent?

Carbon credits rely on the assumption that forests will store carbon over the long term. However, fires destroy this permanence, turning credits into empty promises. According to the Berkeley Goldman School for Public Policy, over 30% of all carbon credits in the market, globally, are forestry & land use based efforts.Who Bears the Risk?

When forests linked to carbon credits burn, who compensates for the lost carbon? Many current frameworks lack robust mechanisms to address this risk, leaving buyers and the climate vulnerable. Typically, projects that are issued ARB offset credits are expected to contribute between 17% and 19% of their total credits into the Forest Buffer Account. In the event of a forest fire, when this carbon is emitted, after the losses are evaluated, a corresponding number of credits are withdrawn from the buffer pool. Between end of 2023 and early 2024, California’s buffer pool lost more than 4 million credits, while it gained only 2.74 million in all of 2022 and 2023 according to CarbonPlan’s analysis. This however contradicts what CARB shows in its report, arguing that the methods used by CarbonPlan are different and not consistent with widely accepted standards.And herein lies a common challenge; every model developed by researchers has a slightly different set of assumptions and risk of forest fires and its impact on the buffer pool can vary.

Double Jeopardy:

Some programs fail to account for future fire risks in their initial calculations, meaning that the true carbon offset value was never accurate in the first place. For example, afforestation projects in fire-prone regions like California underestimated wildfire risks, as seen in the 2020 Zogg Fire, which destroyed forested areas linked to carbon credits. Similarly, in Australia, the 2019-2020 bushfires released over 830 million tons of CO2, negating years of carbon sequestration efforts tied to credits. REDD+ initiatives in the Amazon have also faced challenges; illegal logging and deliberate agricultural fires reduced the forest’s carbon sink potential and undermined the credibility of related credits. These examples underscore the critical need for robust risk assessment in carbon credit programs to ensure their integrity and effectiveness.

Time for a Carbon Credit Overhaul & Scrutiny

The increasing frequency and intensity of forest fires reveal a hard truth: forest-based carbon credits are not the climate solution we hoped they would be. While forests remain vital to combating climate change, tying their protection to carbon markets has inherent risks that cannot be ignored.

What Needs to Change?

Diversify Offsets: Relying heavily on forests for offsets is a risky strategy. Carbon credits should be expanded to include more resilient solutions, like direct air capture or soil carbon sequestration. Biochar has emerged as a frontrunner and an alternative to tree/forest-based caron sequestration; Google recently announced the largest biochar deals to-date.

Mandatory Fire Buffers: Programs issuing forest-based credits should mandate buffer zones and fire-resistant management practices to reduce fire risk. The challenge however is how and who leads this guidance from a practical standpoint.

Insurance Mechanisms: Buyers of carbon credits should require insurance to cover potential losses from wildfires, ensuring their investment retains value. In fact in June 2024, carbon insurance company, Kita, and UK-based carbon standard, Wilder Carbon announced a “first ever” insurance policy for a buffer pool, with capacity provided by specialist (re)insurer, Chaucer.

Focus on On-Site Emissions Reduction: Instead of leaning on offsets, corporations and governments should prioritize direct emissions reductions, leaving carbon credits as a supplementary tool, not a primary strategy. With over 42% of Fortune 500 companies stating that they plan to use carbon credits as a means to get to their ESG goals, it is quite concerning to see the somewhat over reliance on carbon offsets half way around the world.

What are your thoughts on the topic?

Infographic of the week - Forest Area Globally

If I assume, based on a variety of data available, that a well preserved acre of forest can sequester 10 metric tons of CO2 per year, using 2018 data from this chart of 4 billion (hopefully well-preserved forest land) hectares could sequester something like ~9.8 billion metric tons of CO2 per year.